Plastic pollution is one of the most pressing environmental issues today. Despite widespread public belief in recycling as a solution, the reality is far more complex. Over decades, the petrochemical and plastics industries have promoted plastic recycling as a sustainable way to manage plastic waste, but the facts show a different picture.

This article outlines the historical and current failures of plastic recycling, the role of the plastics industry in misleading the public, and the data that proves plastic recycling has been an ineffective solution from the start.

In this article

The Scale of the Plastic Waste Problem

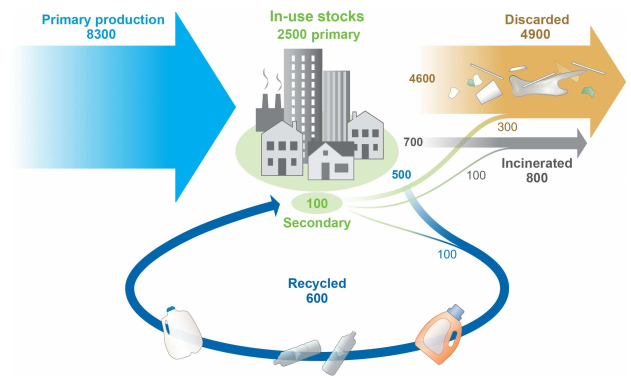

Since the large-scale production of plastics began around 1950, plastic has become a cornerstone of modern life. Over 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic have been produced globally, with production accelerating dramatically over the past few decades.

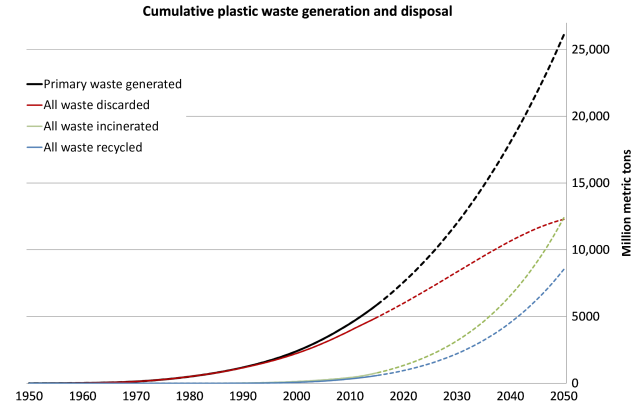

By 2015, the world had generated approximately 6.3 billion metric tons of plastic waste, but only 9% of that waste had been recycled. Most plastic waste—about 79%—either ended up in landfills or was discarded into the environment, where it continues to accumulate in ecosystems across the globe.

The scale of plastic waste is staggering. At current rates, by 2050, an estimated 12,000 million metric tons of plastic waste will be sitting in landfills or polluting natural environments. This persistent accumulation of waste is due to the very nature of plastic—it is durable and resists biodegradation, making it a long-lasting pollutant. Even plastic that is recycled doesn’t escape the waste cycle, as it is usually “downcycled” into products of lower quality that are eventually discarded.

Why Most Plastic Can’t Be Recycled

Despite decades of emphasis on recycling, only a small fraction of plastic is ever actually recycled. The reality is that most plastics cannot be recycled, and those that can are only recyclable under very specific conditions.

This is due to several factors:

- Chemical Composition: Plastics are made from various polymers, each with different chemical properties. The most commonly recyclable plastics are Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) and High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE), labeled as plastics #1 and #2. These are the types of plastics used for products like water bottles and milk jugs. However, these only represent a fraction of the total plastics in circulation. Most other types of plastics—labeled #3 to #7, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polystyrene—have no end markets or facilities capable of effectively recycling them.

- Additives and Contaminants: Many plastic products are made from complex mixtures of materials, including plastic polymers, metals, paper, and adhesives. Even plastics made entirely from one type of polymer may have chemical additives or colorants that render them unsuitable for recycling. For instance, clear PET bottles are recyclable, but PET bottles tinted green or other colors cannot be recycled alongside them.

- Degradation in Quality: Plastics degrade with each cycle of being melted down and reprocessed. This means that recycled plastics are often weaker and of lower quality than virgin plastics, making them less desirable for manufacturers. This process of “downcycling” limits how many times plastic can be reused before it is ultimately discarded.

Because of these limitations, the recycling rate for plastic in the United States has never exceeded 9.5%, and as of 2021, it has fallen to a mere 5-6%. The remainder is either incinerated or placed in landfills, contributing to pollution rather than solving it.

The Petrochemical Industry’s Role in Perpetuating the Recycling Myth

The failure of plastic recycling is not new knowledge. For decades, the plastics and petrochemical industries have known that plastic recycling was technically and economically unfeasible, but they continued to promote it as a solution to plastic waste.

The motivations for this are clear: promoting recycling allowed the industry to avoid stricter regulations and maintain demand for virgin plastic production.

In the mid-1980s, the plastics industry faced increasing public pressure due to rising awareness of environmental issues and a growing backlash against single-use plastics. To deflect calls for bans and stricter regulations, the industry launched a coordinated campaign to promote recycling. Industry groups such as the Society of the Plastics Industry (SPI) and newly created entities like the Plastics Recycling Foundation (PRF) worked to convince lawmakers and the public that recycling was a viable solution.

In reality, internal documents from the industry show that the challenges of plastic recycling—such as the cost of collecting, sorting, and processing, as well as the lack of markets for recycled plastic—were well understood. For example, by the 1980s, the industry knew that the cost of recycling plastic was often higher than producing new plastic from fossil fuels. Yet, despite this knowledge, the industry continued to promote recycling as the answer to plastic waste.

One of the industry’s key strategies was the introduction of Resin Identification Codes (RICs) in 1988. These numbers, enclosed in a triangular recycling symbol, were intended to make it easier for consumers and recyclers to sort plastics by type.

However, the RICs had the unintended effect of misleading the public into believing that all plastics were recyclable, when, in fact, most are not. Recyclers themselves expressed opposition to the system, as it added confusion without solving the underlying issues.

RELATED: Why Biodegradable Plastics Are Urgently Needed to Revolutionize the Packaging Industry

The Failure of “Advanced Recycling” Technologies

In response to renewed public concern over plastic pollution in recent years, the industry has shifted its messaging to focus on “advanced recycling,” also known as chemical recycling. This process uses heat or chemicals to break plastics down into their basic components. However, despite being touted as a new solution, advanced recycling faces many of the same issues as mechanical recycling.

Most advanced recycling processes are inefficient, with as little as 1-14% of the plastic material being turned into new plastic, while the rest is converted into fuel or waste. Moreover, the cost of advanced recycling is prohibitively high—1.6 times the cost of producing new plastic. These processes have yet to prove that they can operate on a large scale without incurring enormous environmental and financial costs.

A Call for Accountability

The global plastic waste crisis cannot be solved through recycling alone, and the decades-long promotion of recycling as a solution has been nothing short of a deceptive strategy by the petrochemical industry. As public awareness of the environmental impacts of plastic pollution continues to grow, it is crucial to hold the industry accountable for its role in perpetuating this myth.

To move forward, we must seek real solutions to the plastic waste problem. This includes reducing the production of single-use plastics, investing in alternative materials, and implementing policies that hold producers responsible for the waste they create. Only then can we begin to address the environmental damage caused by plastic waste.

By understanding the limitations of recycling and recognizing the deliberate efforts to obscure these limitations, we can make more informed decisions and push for policies that truly tackle the root causes of plastic pollution.

References

The Fraud of Plastic Recycling, CCI (PDF), February 2024

Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made, 2017

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE: The Hidden Costs of Renewable Energy