The Great Pacific Garbage Patch has long been the poster child for ocean plastic pollution, capturing public imagination and spurring global concern. However, a groundbreaking investigation by Elizabeth, a seasoned journalist with months of research and expert interviews under her belt, reveals that much of what we think we know about ocean plastic is based on misconceptions, oversimplifications, and in some cases, outright falsehoods.

“You’re being lied to about ocean plastic,” Elizabeth asserts, setting the stage for a series of revelations that challenge our understanding of this environmental crisis.

In this article

The Myth of the Trash Island

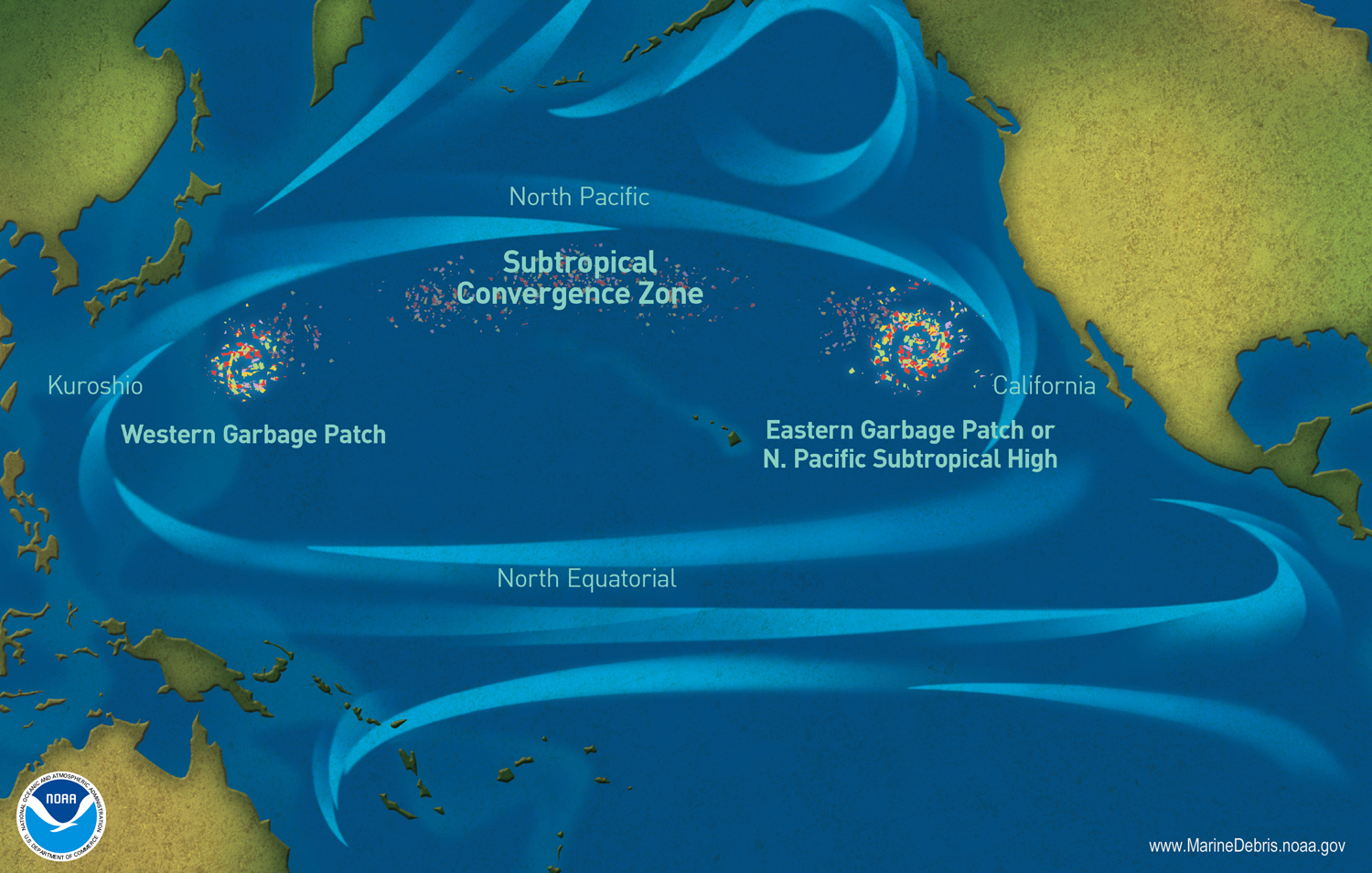

Perhaps the most pervasive myth is the visual representation of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Widely circulated images show islands of trash with visible landmasses in the background, creating a dramatic but entirely misleading picture. Elizabeth explains, “When you see pictures like this, where there’s clearly mountains or maybe islands in the background, that is obviously not the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.”

In reality, the patch is a vast, swirling vortex of plastic that is largely submerged and not easily visible from the surface. It’s a dynamic entity that moves and changes with ocean currents, defying simple visual representation. This misconception has led to a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature and scale of the problem.

Surprising Origins of Ocean Plastic

One of the most startling findings from Elizabeth’s investigation concerns the origin of plastic in the patch. Contrary to the popular narrative that it’s primarily composed of everyday consumer waste, a 2022 study revealed that 75-86% of the macroplastics (items larger than 5mm) in the garbage patch actually come from the fishing industry.

This finding challenges the narrative that has long placed the blame squarely on individual consumers. “It was talked about as another shame-on-us kind of thing,” Elizabeth notes, “and it was assumed that it must be all of our daily household plastic that was in the garbage patch.”

The Littering Myth

Another pervasive myth that Elizabeth’s research debunks is the focus on individual littering as a primary cause of ocean plastic pollution. According to data from the OECD, littering accounts for only a tiny fraction of plastic entering the environment. Instead, mismanaged waste – which includes illegal dumping and open burning – is responsible for 82% of macroplastic leakage into the environment.

Key Findings from the OECD study:

- Mismanaged Waste: This category encompasses waste that is not disposed of adequately, which includes practices such as illegal dumping and open burning. In 2019, it was estimated that this type of waste was responsible for 86% of all plastic leakage into the environment.

- Littering’s Minor Role: In contrast, littering contributes only a small fraction to the overall plastic pollution problem. While littering is recognized as a growing source of macroplastic leakage, it is projected to reach approximately 2.3 million tons annually by 2060, which is significantly lower compared to the leakage from mismanaged waste.

- Projected Increase: The leakage from mismanaged waste is expected to increase dramatically, with projections indicating that it will rise from 6.1 million tons per year in 2019 to 11.6 million tons by 2060. This emphasizes the need for improved waste management strategies.

This shift in perspective puts pressure on systemic issues and large corporations. Elizabeth points out that Coca-Cola has been named the top plastic polluter for six consecutive years, responsible for 11% of all branded plastic pollution found on beaches. Even more staggering, just 56 companies are responsible for half of the world’s branded plastic pollution.

The Recycling Fallacy

Recycling, often touted as a solution to plastic pollution, is revealed to be largely ineffective in Elizabeth’s investigation. Global recycling rates remain stubbornly below 10%, and only about 18% of plastic leaking into the ocean is potentially recyclable.

“Recycling was doomed to fail because it was given an impossible task, and the impossible task was to just keep up with limitless plastic consumption,” Elizabeth explains. This doesn’t mean we should abandon recycling entirely, but it does call for a radical rethinking of our approach to plastic use and disposal.

Hidden Sources of Microplastics

The investigation also sheds light on often-overlooked sources of microplastics. While clothing and personal care products have long been recognized as contributors, recent research has identified two surprising major sources: tires and paint.

Tire wear is estimated to account for 9% of all plastic pollution entering the ocean. Each tire on a car loses about a kilogram, or 2 pounds, of tire dust over its lifetime. Heavier vehicles, such as SUVs popular in the United States, contribute even more to this problem.

As tires wear down, they release tiny rubber particles into the environment. Studies indicate that tire particles can have harmful effects on aquatic organisms. For instance, exposure to these particles has been shown to alter swimming behavior and limit growth in species such as the Inland Silverside and mysid shrimp. Additionally, toxic leachates from tires, particularly the chemical 6PPD-Quinone, have been linked to high mortality rates in fish like coho salmon.

Tires also contain over 400 chemicals, including heavy metals like copper and lead. When tires degrade, these toxic substances can leach into waterways, posing risks to both aquatic life and human health. The breakdown of 6PPD, used in tires to prevent cracking, transforms it into highly toxic compounds that can be lethal to various fish species.

Even more surprisingly, paint may be an even larger source of microplastics. According to recent research, approximately 40% of paint ends up in the environment, and about 37% of paint is composed of plastic polymers. “We’re painting our walls with plastic,” Elizabeth notes, highlighting the pervasive nature of the problem.

Paint used in various applications contributes to microplastic pollution when it degrades. As paint breaks down over time due to environmental exposure, it releases plastic polymers into the water.

The microplastics from paint can accumulate in marine ecosystems, potentially affecting a wide range of marine organisms. The exact impacts are still being studied, but the presence of microplastics in marine environments is known to disrupt the food chain and harm aquatic life.

The Global Response

As the world grapples with these issues, a pivotal moment has arrived with the UN’s “End Plastic Pollution” resolution. However, negotiations for a global treaty are being complicated by the interests of the petrochemical and fossil fuel industries, which see plastics as crucial for their future growth.

Scientists and activists are calling for two main actions: reducing plastic production and simplifying the chemicals used in plastics. Currently, about 16,000 chemicals are used in plastics, most of which are not regulated by international law.

Despite these efforts, plastic production is set to triple by 2060, according to current projections. The investigation reveals that major chemical companies like Dow are planning for continued growth in plastics, with a 20% increase in volumes since 2019.

The Road Ahead

As this complex issue unfolds, it’s clear that addressing ocean plastic pollution will require a multi-faceted approach that goes beyond individual actions to encompass systemic changes in production, waste management, and international policy.

Elizabeth’s investigation reveals that the truth about ocean plastic is far more nuanced and challenging than most people realize. It calls into question many of our assumptions about the problem and highlights the need for a radical rethinking of our relationship with plastic.

From rethinking the composition of paints and tires to addressing the vast quantities of fishing gear polluting our oceans, the solutions to this crisis will require innovation, collaboration, and a willingness to challenge the status quo.

As we move forward, it’s crucial that we base our efforts on accurate information and a comprehensive understanding of the problem. Only by confronting these uncomfortable truths can we hope to make meaningful progress in the fight against ocean plastic pollution.

References:

Global Plastics Outlook, OECD, 21 Jun 2022

RELATED: Groundbreaking Lawsuit Targets ExxonMobil for Decades of Plastic Recycling Deception